|

The Jay Ballers

of the World

A

History of Ballplayers Named Jay,

Part I: Pitchers

Six and a half

years ago, when I first got hooked up to the Internet and made my own home page

(thankfully long gone), another man sharing the name Jay Jaffe emailed me. "Who

are you and why are you using my name?" asked an indignant Jay M. Jaffe, who turned

out to be, by his own description, "the (reasonably successful) 52 year old head

of a marketing consulting firm in Washington D.C." Since then, I've discovered

that I have even more company in the Jay

Jaffe club. But if my thirty-two years on this earth have convinced me of

one thing, it's that I'm the REAL Jay (Steven) Jaffe. At least on this website.

Growing up, I didn't

know anybody else who shared my first name, a circumstance which produced feelings

of uniqueness (at best) and loneliness (at worst; I was a bit envious of boys

with more popular names). The only ballplayers I knew of with the name Jay were

Jay Johnstone, a flaky pinch-hitter who became a minor celebrity author ("writing"

two books) thanks to a pinch-hit home run in the 1981 World Series for the L.A.

Dodgers, and Jay Peters, a AAA outfielder in the Angels chain who played at Salt

Lake City in the late '70s and led the league in sweatbands, and whose career

was never the same after a mid-season broken leg.

Today, I'm much

more secure with my name. I once worked at a company in which I was one of three

Jays, and I now have several Jays to look to on the ballfield (and no, I've never

felt any special love for the Toronto Blue Jays). In fact, it turns out that the

name Jay is more popular than ever among big-league ballplayers. Six Jays played

in the majors last season (Bell, Buhner, Gibbons, Payton, Powell, and Witasick),

and four played in 2000 and couldn't have strayed too far from the show (Canizaro,

Ryan, Spurgeon, and Tessmer). With the help of Baseball-Reference.com,

I pulled out a list of all of my ballplaying namesakes. As somebody who enjoys

hustling out even my flakiest digressions as if they were sharp liners off the

wall, I now share my study with you. Of the 38 ballplayers who've gone by the

first name (throwing out Joey Jay and Jayhawk Owens--both offered up by the BR

search engine—for obvious reasons), half of them have played during my 31-year

lifespan. But they go as far back as Jay Pike (1877).

In some cases,

my research didn't go much further than the Internet would take me. But thanks

to the wonders of Baseball-Reference,

Retrosheet, the

Baseball Library and other sites around the web, I've managed to compile capsule

histories of each of the 38 ballplayers who share my first name (even if it was

actually their nickname). Even with those limited resources,

I was able to find out a fair amount about these Jays. What strikes me in examining

this cross-section of ballplayers is how brief some of their major-league careers

were (13 of the 38 played less than 10 games). A poignant theme seems to run through

the tales of these men—full of promise and auspicious beginnings (two Jays,

Bell and Gainer, homered on their first big-league pitch), occasionally scaling

the peaks of glory (Bell scored the winning run in Game 7 of the 2001 World Series,

Powell garnered the win in Game 7 of the 1997 Series), more often than not finding

their dreams dashed all too early, yet some of them willing

to go to the ends of the earth to stay in the game they loved—Japan, Mexico,

Taiwan, Italy, Thunder Bay—or to keep alive a faint hope of making it back

to the Show.

Rather than risk

lulling you to sleep, I've split this into two pieces—the pitchers here,

and the hitters in a piece to follow. At the bottom of the page are career stats

for these pitchers, courtesy of Sean Forman at baseball-reference.com. Clicking

on the player's name takes you to his page at BR.

One more thing:

since my name isn't going to change anytime soon, this is an ongoing project which

I will update from time to time. If any of you out there have information about

any of these ballplayers which you'd like to share for this article, please email

me at jay@futilityinfielder.com.

Jay Aldrich:

Currently tied for 62nd place on the Milwaukee Brewers' all-time list for saves,

only 132 behind Dan Plesac.

Jay Avrea:

Real name James Epherium Avrea. Nearly 30 years old when he debuted. Had almost

nothing to do with the Cincinnati Reds 66-87 record in 1950.

Jay Baller:

On December 9, 1982, Baller was one of five Phillies (Manny Trillo, Julio Franco,

George Vuckovich, and Jerry Willard were the others) sent to Cleveland in a controversial

deal for Von Hayes. After his major league days were over, he served a bitter

stint in the Mexican League and then headed for Japan, where he was a teammate

of Ichiro Suzuki on the Orix Blue Wave in 1994.

Jay Dahl:

This one's a chiller. Signed by the Houston Colt .45s in June of 1963, at the

tender age of 17, Dahl showed promise with a 5-1 record and a 1.42 ERA at Moultrie

of the Georgia-Florida League. So much promise that Dahl got called up, and was

the starting pitcher for the Colt .45s when they fielded the first all-rookie

nine in baseball history on September 27, 1963. The rookies, who included Joe

Morgan, Rusty Staub, and Jerry Grote, got pounded by the New York Mets 10-3, and

Dahl, knocked out in the third inning, took the loss. Unable to pitch in 1964

due to a back injury, he played in eleven games as an outfielder with Statesville

in the Western Carolinas League. Returning to the Western Carolinas League in

1965, this time with Salisbury, he had regained his pitching form with a 5-0 record.

The day after he won his fifth game game, he was killed in an auto accident which

killed another passenger and blinded a teammate of his. He was 19 years old. There's

an obituary

on The Astros Daily website.

Jay Franklin:

Real name John William Franklin. The overall #2 pick by the San Diego Padres in

the June 1971 draft, Franklin was chosen before players such as Jim Rice, Frank

Tanana, George Brett, Ron Guidry, Mike Schmidt and Keith Hernandez. Called up

to the show in September, in his only start he gave up career home run #638 to

Hank Aaron. Young pitching will break your heart.

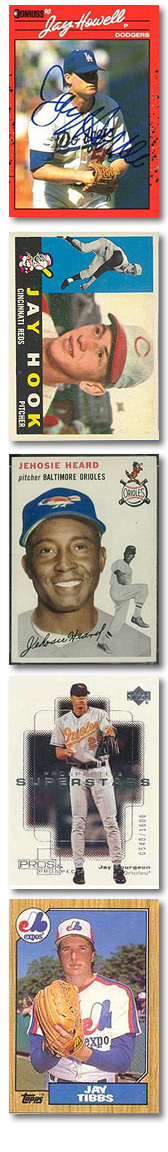

Jay Heard:

Real name Jehosie Heard. A Negro League veteran, he played for the 1948 Birmingham

Black Barons of the Negro American League, where he was a teammate of a rookie

named Willie Mays. The Black Barons won the final Negro League World Series that

year, as the Negro National League folded following the season. He only appeared

in two games, but Heard was the first black player for the Baltimore Orioles—though

the franchise had fielded black players while it was based in St. Louis.

Jay Hook:

A bonus baby signed in 1957 by the Reds out of Northwestern (where he was an engineering

student), Hook struggled in parts of five seasons with Cincinnati—his best

was an 11-18, 4.50 ERA campaign in 1960. Cutting their losses, the Reds exposed

him in the 1962 expansion draft, and he was selected by the New York Mets. He

didn't do horribly, given the historically dismal circumstances; he recorded the

franchise's first victory (after they'd lost their first nine games), and as their

number three starter behind Roger Craig and Al Jackson, went 8-19 with a 4.84

ERA. That performance was actually 1.5 wins above what the Mets could have been

expected to win without him in the same number of decisions.

Hook's renown with

the Mets came when he wrote an article for Sport Magazine about why a curveball

curves. The joke, of course, was that "he had a hard time getting the message

though to his arm," as the authors of the Great American Baseball Card Flipping,

Trading, and Bubblegum Book put it. Casey Stengel called him "the smartest

pitcher in the world until he goes to the mound." Hook folded up his slide rule

and went home after a 4-14 campaign and then a batting-practice-esque three appearances

in 1964. He received his Masters degree in thermodynamics from Northwestern and

took a job with Chrysler, later returning to his alma mater as a visiting professor

and a board member of their engineering school. The Old Professer would have been

proud.

Jay Howell:

The most famous, or infamous, of all the Jay pitchers, Howell became the Dodgers

closer in 1988 after bouncing around to varying degrees of success with the Reds,

the Cubs, the Yankees, and the A's. Up to that point, his two big claims to fame

were losing the 1987 All-Star Game and being involved in one of the decade's biggest

trades, when Rickey Henderson, another player and cash were sent from the A's

to the Yankees for Jose Rijo, Stan Javier, Tim Birtses, Eric Plunk and himself.

Though he did well in Oakland, a season-ending injury opened the door for converted

starter Dennis Eckersley to try his hand at closing. Having lost his job, Howell

was traded to the Dodgers with Alfredo Griffin for Bob Welch and Matt Young in

December 1987.

As the Dodgers'

closer, Howell finished the 1988 season on a hot streak, going the last seven

weeks of the season without allowing a run as the Dodgers took the NL West. He

achieved his notoriety with a trying postseason. In Game 1 of the NLCS against

the Mets, both his and fellow Dodger pitcher Orel Hershiser's scoreless streaks

were broken—they surrendered three runs in the ninth inning, and Howell took

the loss. In his next appearance, in a rainy Game 3, he was ejected for illegally

having pine tar on his glove. The National League suspended him for three games,

though the penalty was reduced to two on appeal. Howell's absence triggered one

of my all-time favorite baseball memories, as Orel Hershiser, who'd pitched seven

innings in defeat the night before, came out of the bullpen in the 12th inningof

Game 5 to shut down the Mets with the bases loaded. After the Dodgers made it

into the World Series, Howell surrendered a game-winning homer to the A's Mark

McGwire in Game 3, but saved Game 4 the next night. He spent another four years

with the Dodgers, three as their closer before losing his job to Roger McDowell,

and bounced from Atlanta to Texas before retiring in 1994.

Jay Hughes:

Real name James Jay Hughes. Broke in with a great Orioles team in 1898 featuring

Wilbert Robinson, John McGraw, Hughie Jennings, Willie Keeler, and Joe Kelley,

going 23-12 with a 3.20 ERA as their second-best starter. He pitched a no-hitter

on April 22, 1898 (another no-hitter, by Cincinnati's Ted Breitenstein, was thrown

the same day, marking the first time that happened). Hughes was transferred to

the Brooklyn Superbas for 1899; the Orioles and Superbas were both owned by the

same people. Jennings, Keeler, and several other key Orioles were transferred,

including manager Ned Hanlon, who had an ownership stake. The owners wanted to

transfer McGraw and Robinson as well, but they refused to leave due to their business

interests and family in Baltimore. In Brooklyn, Hughes was the National League's

second-best pitcher behind Hall of Famer Vic Willis in 1899. He led the circuit

with 28 wins (against 6 losses) and an .824 winning percentage, and posted the

5th best ERA. He had two more respectable seasons, then disappeared from the game.

Fell from a train and fractured his skull, dead at 50.

Jay Parker:

Faced only three batters in his single major league game, walking two and plunking

one; sources differ as to whether or not the runs scored (CNNSI,

Baseball Almanac and my old MacMillan Baseball Encyclopedia say yes,

baseball-reference says no; I've gone with the majority opinon and altered the

stats in the table below). Bad pitching ran in the family; his older brother Doc's

final game, in 1901, was an eight-inning, 26-hitter in which he allowed 21 runs

(14 earned), walking two and striking out none. The 26 hits and 21 runs allowed

still stand as National League records. Ouch.

Jay Pettibone:

Given four starts in September for a mediocre Twins team in 1983, Pettibone ran

the table, going 0-4. His first

start was a heartbreaker. Holding the Kansas City Royals to a 1-1 tie into

the ninth, he got two outs, then allowed a single to Hal McRae and a 2-run homer

to Willie Aikens. Amazingly enough, two starts later, Pettibone was victimized

again by the same hitter! Aikens broke a 1-1 tie with a solo homer in the seventh.

Two batters later, John Wathan hit an inside-the-park homer. Aikens was nowhere

near Pettibone's other two losses, neither of which was quite so cruel. Pettibone

later turned up to audition as a replacement player for the California Angels

during the spring of 1995. According to this

article, he was working at the time as a special agent for the U.S. Treasury

Department. I wonder what the hell that entails.

Jay Powell:

Very solid middle reliever. A mainstay of the Florida Marlins bullpen during their

1997 championship season, he appeared in 74 games with a 7-2, 3.28 ERA performance.

He capped it all by being the winning pitcher in Game 7. When the Marlins were

imploded at the behest of scumbag owner Wayne Huizenga, he was traded to Houston.

He's had some solid seasons since then, last year appearing in 74 games split

between Houston and Colorado (his 3.24 ERA in those two pitching hellholes translates

to a 150 ERA+ for the year, thank you very much). He cashed in with a 3-year,

$9 million deal with the Rangers this winter. Greaaaaat, another pitchers' paradise.

Jay Ritchie:

Breaking in with the Red Sox in 1964, he was a useful reliever for a couple of

seasons before being traded to the Braves for a pair of skis—Bob Sadowski

and Dan Osinski (Lee Thomas was actually the main Boston player in the deal).

Over a four-game stretch in 1967, he retired 28 straight batters, or one more

than a perfect game. Traded to the Reds the next season, he was much less successful.

According to a friend of his, he's now a successful automobile salesman in his

hometown of Salisbury, North Carolina.

Jay Ryan:

Back when I lived in Providence, Rhode Island, I entertained visions of a freelance

writing career focused on music. In my first (and only) paid article, I profiled

a Providence band called Six

Finger Satellite for Option magazine. Six Finger Satellite's lead singer

was named J. Ryan (short for Jeremiah); he stood 6-foot-7 and could really scream

over a wall of guitars and Moog synthesizers. But he was a nice guy, otherwise.

I'm sure this Jay Ryan (real name Jason Paul Ryan) is a real nice guy too, but

he can't pitch for shit. In 66.2 big league innings, he's allowed 17 homers, or

one every 3.9 innings. Spent last year at the AAA level split between Nashville

(Pirates affiliate) and Las Vegas (Dodgers affiliate) compiling a 3- 8 record

with a 6.42 ERA. He might want to consider a singing career instead.

Jay Spurgeon:

After pitching well enough to win the Jim Palmer Prize as the Orioles Minor League

Pitcher of the Year, he got a taste with the Orioles in 2000. Following two relief

appearances, he won his first start, pitching seven strong innings against Tampa

Bay. He started the 2001 season at Rochester, where he was only marginal (3-5,

4.55 ERA in 15 starts). The decimated Orioles called him up for a week but he

didn't get into a game. Returning to the minors, he dislocated his non-throwing

shoulder fielding a bunt and required surgery, shelving him for the season.

Jay Tessmer:

Postcards from the It's All Downhill From Here department. Debuted with the 1998

Yankees in late August, he nabbed an extra-inning win against the Angels. With

the division long sewn up, he got into six more ballgames and pitched reasonably

well. Or at least well enough to distinguish him from the immortal likes of Mike

Buddie, Mike Jerzembek, Ryan Bradley, Joe Borowski, and Jim Bruske—in my

mind at least. He spent the next two seasons with a stranglehold on the closer's

job... in Columbus. Though he led the International League with 28 saves in '99

and racked up 34 in in 2000, he didn't fare well in his limited tastes of the

Bronx. Sporting a career 7.77 ERA, the Yankees shipped him to Colorado, not exactly

the place to fix that kind of thing. Failing to crack the Rockies' roster in the

spring of 2001, he was shipped out to Colorado Springs, where he lit up things

to the tune of a 6.59 ERA (hey, it's the altitude) before being traded to the

Indianapolis Indians (the Milwaukee Brewers AAA affiliate). He settled down, winning

seven games and saving four, with a 2.79 ERA. But if he can't crack the measly

Brewers staff this year, things don't look good for our Jay.

Jay Tibbs:

Originally drafted by the Mets in 1980, he was traded to the Reds in 1984. As

a 22-year old rookie for the Cincinnati Reds, he went 6-2 in 14 starts and impressed

enough to earn spot in the team's '85 rotation. But he went 10-16 with a 3.92

ERA and was shipped off to the Expos. Two seasons of proving himself a below-average

starter north of the border, he was sent to Baltimore in 1988. Starting the season

in the minors, he had nothing to do with their 21-game losing streak to open the

season, but he made up for his tardiness by posting 15 losses for a team that

posted 107 overall. He did help in their turnaround the next season, winning once

in late May and four times in June. But he seems to have dropped off the face

of the earth for the rest of the season, following his next start. He'd lost the

magic when he resurfaced the next season, going 2-7 before being traded one final

time, to Pittsburgh. His 16 losses remained a low-water mark of sorts for the

Reds until Steve Parris lost 17 in 2000. 'Tis sweet to be remembered, as Flatt

& Scruggs once sang.

Jay Witasick:

Real name Gerald Alfonse Witasick. Last summer, for one brief and shining half-season

in San Diego, he performed as if he were not just a servicable middle reliever,

but an unhittable one. This was in direct contradiction to the three years he

spent trying to crack the A's staff and two years posting high-5 ERAs for the

Royals. San Diego cashed him in before the bubble burst, liberating touted (but

somewhat damaged) prospect D'Angelo Jiminez from the Yankees. He quickly reverted

to form in the Bronx, and assured his departure by allowing eight runs in 1.1

innings in relief of Andy Pettitte in a nightmarish Game 6 of the World Series.

All told, he did post a 3.30 ERA in 79 innings in 2001, striking out 106. The

Yanks managed to get something useful in exchange for Gerry over the winter, trading

him to San Francisco for John Van Der Waal. A couple boxes of baseballs would

have been fine, really.

|

|

|