|

||||||||

|

||||||||

|

||||||||

| All contents of this web site © Jay Jaffe, 2001-2011 except where indicated. Please contact me for any questions or comments regarding this site. |

|

L E A D I N G O F F |

AUGUST

27 ,

2005

|

|||||

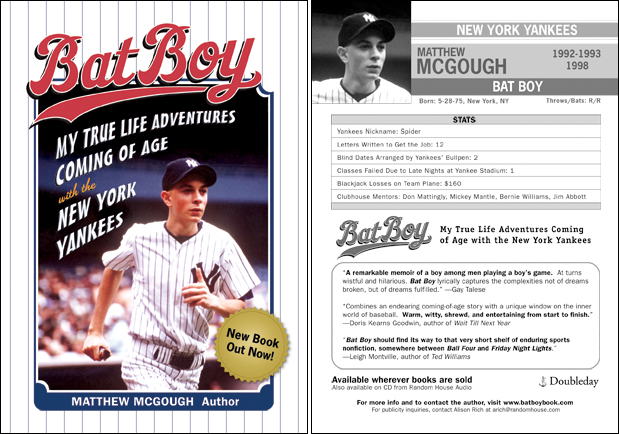

Bat

Boy Chapter 4 With school finally out of the way and my summer days free again, the most beguiling clubhouse perk ballooned in my imagination: being invited by Nick to join the Yankees on a road trip. Jamie had traveled on the team's swing out to Seattle, Oakland and Anaheim after the All Star Break, and he returned home so elated with the experience that I didn't even need to hector him into telling me about it. For weeks afterward, Jamie freely volunteered details of the eleven-day luxury tour. The six-hour flight on the Yankees' chartered jet. The deluxe hotel suite he'd stayed in (albeit a deluxe hotel suite shared with Nick). The strangeness of wearing a road uniform instead of the home pinstripes. The long nights out on the town that the players had taken him on in each of the three cities they'd visited. The problem for me was that joining the team on a road trip was a privilege usually accorded only to second year batboys, as a reward for a season's worth of hard work. Asking Nick to make an exception in my case seemed out of the question; Robby and the Mule agreed that making a direct appeal to Nick would just about kill my chances. Still, as the only member of the clubhouse staff who hadn't yet traveled that season, they suggested a scenario in which Nick might feel obligated to take me on a trip, even a short one, before the season ended. "Work hard," the Mule advised me. "Let the old man see you really busting your ass, and maybe he'll take you along." I hustled to put in time outside of game days, working without pay. I showed up at the ballpark on off days, when the Yankees occasionally held extra batting practice for struggling hitters, and spent those afternoons shagging flies in the outfield and cleaning up the clubhouse after B.P. I began helping out on unpacking nights, when the Yankees flew back to New York after the end of a road trip. The team usually arrived at an ungodly hour, in the middle of the night or very early in the morning. If the Yankees finished a series in, say, Chicago with a night game ending there at ten o'clock, you could count on the team needing one hour after the game to shower and pack (eleven o'clock) and an hour to get to O'Hare Airport (twelve o'clock). Counting the time for the flight back to New York, plus the hour time differential, two or two-thirty, and then the bus ride from the airport to the Stadium, the team rarely arrived home earlier than three or three thirty in the morning. I waited with Rob and the Mule in the clubhouse for the ballplayers, their equipment, and Nick to appear. And that's what time the night's work began. Unpacking nights left you the following day with jet lag-like symptoms as pronounced as if you'd crossed those time zones yourself. Still, mindful of the dwindling number of road trips left on the Yankees' schedule before the end of the season, I met the team every time they came off the road in August. But with the beginning of the school year looming, no invitation from Nick seemed forthcoming. • • • It was clear by early September that the Yankees were not going to catch the Toronto Blue Jays in first place. After a stretch in which New York lost thirteen of sixteen games, even some of the most affable ballplayers on the roster couldn't hide their frustration with the turn the season had taken. I saw Mattingly lash out at a pair of front office interns who were indiscreetly laughing and joking in the clubhouse after a close loss. Nick escorted the interns, white as ghosts for having offended the Yankee captain, to the clubhouse door. A week or so later, Steve Farr, the Yankees' closer, capped a disastrous performance by the team's relief staff by destroying the big-screen television in the middle of the clubhouse. The bullpen inherited a 6-1 lead against the Oakland A's in the top of the sixth inning and promptly gave up a grand slam to Jose Canseco. Farr, a rough-around-the-edges, Harley-Davidson-riding guy with a Fu Man Chu mustache, came into the game in the top of the ninth, charged with preserving the now tenuous one run lead. He allowed a single, a walk, and then, facing Oakland third baseman Carney Lansford, left a 3-2 pitch out over the middle of the plate. Lansford deposited the ball in the left field seats for a three-run home run. Upon entering the clubhouse after the game, Farr took a baseball bat to one of the concrete posts supporting the clubhouse roof. The concrete thankfully proved too durable to deliver the visual results Farr probably felt necessary for the catharsis he was seeking, and after a few thwocks, he went in search of something more satisfyingly fragile. The Mule was standing in front of his locker, close by the entertainment center, and I watched his eyes widen as Farr's intentions became apparent. The television was tuned to the Yankee post-game show, and the sportscaster was narrating video of the Yankees' meltdown. Farr's first swing went through the glass screen of the television, ruining the hopes of the one or two people in the room who may been looking forward to watching more post-game analysis. Farr's second and third swings, two-handed and over the top, splintered the set's casing, scattering plastic and metal parts on the clubhouse floor across a ten-foot radius. Nick signaled the security guard at the door to hold the press outside the clubhouse until it was clear Farr was done, but it seemed like a moot gesture; I'd have guessed the ruckus was loud enough to be heard all the way to the Grand Concourse. Such eruptions were common enough that we had a name for them in the clubhouse: "snapping." The targets were usually humble: the concrete pillars in the clubhouse; the oversized orange Gatorade tubs in the dugout. There is also a small bathroom located just off the dugout that ballplayers use during games to avoid walking all the way back to the urinals in the clubhouse. The bathroom is fronted by a heavy steel door, and visible on its face are dozens of dents, evidence of baseball bat beatings administered by frustrated Yankee hitters in the moments after bases-loaded strikeouts, popped-up sacrifice bunts and inning-ending double plays. Nobody acknowledges a snap while it's happening. A ballplayer might be splintering a bat against the bathroom door, cursing at the top of his lungs, and yet everyone would stare straight ahead, carrying themselves as nonchalantly as during pre-game warm-ups. The mess left behind would be cleaned up either by the grounds crew or the batboys, and the game would go on as if nothing had happened. A violent and ferociously noisy outburst, ten feet away? Where? But I'd yet to see a snap as explosive and imaginative as Farr's. At the sound of shattering glass, every head in the clubhouse turned in the direction of Farr and the shattered television; I think even Nick was impressed, if that's the right word. Within a few moments, though, even before Farr tired himself out, dispassion (or at least the appearance of it) returned to the clubhouse. Farr dropped the bat and walked to the trainer's room to have his pitching arm wrapped in ice. The rookies and coaches continued to pick at their plates of mixed greens and baked ziti from the post-game spread. Rob and the Mule ineffectually ran a pair of vacuums over the shards of glass and plastic on the clubhouse carpet for a while, then finally just gave up and taped off the area. The media was ushered into the clubhouse. There was no ignoring the gaping hole where the TV normally droned as players toweled off and got dressed in their street clothes. Ducking under the tape to retrieve dirty spikes from a pair of nearby lockers, I could hear the debris crunch under the soles of my sneakers. "What happened?" one of the Yankees' beat writers whispered to me as I passed by. I shrugged. "Don't know," I said. The next afternoon, Farr walked into the clubhouse and laid five hundred-dollar bills on Nick's table. "Let me know if it costs more than that," he said, loud enough for his voice to carry across the clubhouse. Nick was hanging uniforms in lockers only a few feet away, but he gave no indication that he'd heard the offer, and showed neither opprobrium for the damage caused nor gratitude for the restitution just made. The next day, there was a new clubhouse television, slightly bigger than the one that been there two games before. • • • The Yankees' mathematical elimination from the pennant race, inevitable for many weeks, actually seemed to lift the mood in the clubhouse. It was too late to make much difference in the standings, but between the pressure that had lifted and a few late-season additions to their lineup, the Yankees started to play better, or at least more spirited, baseball. Major league rosters are normally capped at twenty-five men, but for the last month of the season, teams are allowed to carry as many as forty active players. When rosters expand, teams with only next year to look forward to promote their best minor league prospects, giving them a chance to face major league pitching or hitting, auditioning them in anticipation of the following year or off-season trade offers. In mid-September, the Yankees promoted the young stars of their top farm team, the Columbus Clippers, which had just won their minor league's championship. Down 4-2 in the deciding game of a best of five series, the Clippers had rallied for three runs in the bottom of the ninth inning to win the game and the AAA International League championship. The next day, half their starting lineup reported to the Bronx, and they carried with them the giddiness of their still recent triumph. The Yankees went to Baltimore and swept a three game series, spoiling the playoff hopes of the second place Orioles. At the Stadium a few days later, an exchange of brushback pitches sparked a bench-clearing brawl with the Chicago White Sox. I stood on the top step of the Yankee dugout and watched the two teams' relief pitchers stream in from the bullpens to join the scrum that had formed between home plate and the pitching mound. The forty-man-strong rosters of the Yankees and White Sox shoved each other around, letting off steam for ten minutes or so, before filing back into their dugouts. It was the second bench-clearing brawl at the Stadium that season, but the first in which I was clear on what my proper role was while the players resolved their differences on the field. The first time, mindful of the Yankee pinstripes I was wearing, I'd nearly gotten caught up in the excitement. Am I supposed to scrap with the batboy in the other dugout? The idea seemed right, very briefly, before I remembered that the kid across the way was just Ray from the other clubhouse, dressed in a visiting uniform. Before I could take ill-advised action of any kind, the Mule came down the tunnel from the clubhouse and told me exactly where batboys were to stay until a resolution was reached on the field: well within in the dugout. "You never went out there during a brawl when you were batboying in Seattle?" I asked him, watching an umpire step between and separate two knots of players. "Are you crazy?" he said. "I'll tell you what would happen if you left the dugout during a brawl. You'd go out there, and after one of the ballplayers finished kicking your ass, Nick'd kick your ass, and then somebody from the front office'd come down and kick your ass. You'd make SportsCenter, dangling from some six-foot-four ballplayer's neck, but it'd be the last you ever saw of your Yankee ID card." • • • With the end of the season on the horizon, the ballplayers began making preparations to leave New York for their off-season homes. The Yankees would end the season with six games on the road, three in Cleveland and three in Boston. A few weeks before the Yankees' last homestand, Tim Burke, one of the Yankees relievers, called me over to his locker. Burke had been traded to the Yankees from the Mets in June, and we'd spoken more than a handful of times. He was a devout Christian, and at one point in the season had given me a paperback book that profiled a few dozen Christian ballplayers, including himself; though it didn't inspire any epiphanies, I'd read the book and appreciated the gesture. "So I was talking to Nick," Burke told me, "and I've got a proposition for you." Burke explained that he lived in New England during the off-season. After the last home game, he would fly with the Yankees from the Bronx to Cleveland and then Boston, but he needed to figure out a way to get his car up to Massachusetts so he could drive home directly from Fenway when the season ended. "Do you have a driver's license?" he asked me. "Sure," I answered. "Well, I was thinking that you might be able to drive my car up to Boston in time to meet us there when we get in from Cleveland. We'll figure out a room for you in the team hotel, and you can catch a ride back to New York with the team when the series is over." "Nick's cool with me coming to Boston?" I said. "I mean, you asked him?" "I did," he said. "He said you're welcome to work the three games at Fenway." "Jesus Christ!" I said, forgetting for a moment who I was speaking with. "I mean: Wow." I called home after the game to ask my parents' permission, fully anticipating that it might be a tough sell. I had graduated from learner's permit to driver's license only a few months before, and I'd never driven a longer distance than the twenty miles between my parents' house and Yankee Stadium. I breathlessly explained first to my Mom and then my Dad how rare it was that I'd be allowed to travel with the team my first season as a batboy. I couldn't hide my excitement at the opportunity, and with some give and take, we settled upon a solution: my Dad would join me for the drive, drop both me and Burke's car off at the Yankees hotel, and then take the shuttle back to New York the same night. I would get my road trip after all. • • • My season-ending road trip was not the only reason to look forward to the last homestand of the season. For the clubhouse staff, the last home series of the year also meant end-of-season tips from the ballplayers, our just reward for six months of demands promptly met and errands well run. Even for the batboys, the tips were not insignificant: Jamie told me that in those three days you could match the salary that you'd made over the course of the whole season. During the Yankees' final homestand, I was handed a dozen checks and nearly as many envelopes of cash, all of which Nick stored for me under lock and key in a safe deposit box in the trainers' room. The players were generous: a check for a few hundred from Tartabull, the highest paid player on the team, and lesser amounts from most the other guys on the roster. As was his custom every season, Mattingly tipped last. After waiting to see what every other player had given, he would always beat the best tip by a hundred bucks. It was a characteristic move for the Yankee captain; a few years later, after a players' strike prematurely ended the 1994 season, Mattingly was one of only two players – Jim Abbott was the other – to seek out the three batboys' home addresses and send each one an end-of-season tip. -- The Yankees had an off day scheduled between their series against the Indians and Red Sox, and the team was to fly to Boston immediately after the last game in Cleveland. The afternoon of the team's flight, my Dad and I took the train together into the City and the subway up to Yankee Stadium. Burke had left the keys to his car with the security guard in the Yankee lobby. It was a Lexus sedan, a nicer car than I'd ever been in before, and my Dad let me take the wheel for the stretch of highway between the New York and Boston city limits. As if by a sixth sense, my Dad could tell without looking over at the speedometer the few times I inched over the speed limit; each time, he shot me a look that almost involuntarily separated my foot from the gas pedal. We made the trip in about four hours, pulling into the team hotel just before dinnertime. My Dad handed the car keys over to the valet and walked me to the front desk of the hotel. I swung the small bag I'd packed up on the counter and gave my name to the hotel clerk. "I'm here with the Yankees," I added, discreetly but proudly. "I'm staying with Scott Kamieniecki." Kamieniecki, one of the Yankees' young starting pitchers, had offered to let me room with him after his wife decided to stay in New York to prepare for their own post-season trip, back to Michigan. The clerk checked my name against the room list prepared by the Yankees' traveling secretary and then slid a key across the counter to me. "Any incidentals will be charged to Mr. Kamieniecki," she said before stepping away to help another guest. "Incidental what?" I whispered to my Dad. "It means stay out of the minibar," he said. "And don't charge anything to the room." I was saying goodbye to my Dad when Bernie Williams and two of the Yankees recently promoted to the majors, Hensley Meulens and Gerald Williams, strolled past us through the hotel lobby. Three of the youngest players on the team, they had come up through the Yankees' minor league system together. I nodded to Bernie as he passed. "I didn't know you were coming on the trip," he said. I started filling him on the task I'd just completed for Burke, then realized I'd failed to introduce my Dad standing next me. "Oh, sorry," I said. "Guys, this is my Dad. Dad, this is Bernie," and indicating Hensley and Gerald by their clubhouse nicknames, "and Bam-Bam. And Ice." "Jim," my Dad said, greeting all three but not tipping his hand as to whether he'd ever before met a Bam-Bam or an Ice. "You sticking around for the weekend?" Bam-Bam asked me. "Yeah," I said. "I'm staying with Kami." "Your Dad coming to the game tomorrow?" Gerald asked. "Unfortunately not," my Dad answered. "I'm flying back to New York tonight." "We'll keep an eye on Matt for you," Bernie said. "I'd appreciate that," my Dad said. "What are you guys up to tonight?" I asked the trio of ballplayers. "Not sure," Bernie said. "We were just going out now to walk around for a while." "Can I suggest Harvard Yard?" my Dad said. "Yeah?" Ice said. "Oh, it's beautiful," my Dad said. "Really a world-class campus. You should take a walk along the Charles –" "C'mon, Dad," I cut him off, suddenly a little embarrassed. "I'm sure these guys don't care about seeing –" Bernie cut me off in turn. "No, no," he said, chuckling. "Maybe we'll check it out." "Have a good time," my Dad told them, then turned to me. "You too," he said, giving me a nudge with his elbow. "Stay out of trouble." "Dad, c'mon, please," I said. "I'll see you guys later," I said to the ballplayers, and we exchanged goodbyes. I walked with my Dad to the front of the hotel. "You all set?" he asked me. "I'll be fine," I said. "Okay," he said. "Thanks for driving." "Thanks for letting me drive." "Be good," he told me. He gave me a quick hug and then hailed a cab to take him to Logan Airport. I spent most of the Yankees' off day with Robby and the Mule, walking around town, checking out two movies, back to back, at a theater down the block from the Yankees' hotel. When I got back to the room, Kamieniecki invited me to grab a bite with him and a few teammates, but I demurred; I explained that I wanted to be well-rested and on the earlier of the two buses scheduled to take the team to the ballpark the next day. Kami seemed amused at my earnestness, and insisted on ordering me a cheeseburger from room service before he left. I woke the next morning to a beautiful late summer Boston day. Nick treated me to lunch at Charley's on Newbury Street. We sat outside at the sidewalk café, and I peppered him with questions about his many previous road trips to Boston. "I'm very big in this town," he told me, his boasts punctuated by raggedy laughs. "Very big in Beantown, Matty. My town. Very big." The early bus was empty save for myself and a handful of the support staff that chronically reports hours before first pitch: Nick, Rob, the Mule, the Yankee medical trainers, one or two coaches. A Red Sox attendant waved the driver down to the far end of Yawkey Way, and the bus dropped us off flush against the brick exterior wall of Fenway Park. We entered through one of the same gates that fans would use to enter the ballpark in a few hours. Unlike at Yankee Stadium, where both clubhouses are underground, the visiting clubhouse entrance at Fenway was off the same concourse that led to the field level box seats. Only a small wire cage and an elderly security guard with a thick Boston accent seemed to separate the visiting clubhouse from the throngs of Red Sox fans that would later pack the ballpark to root against the hated Yankees. If this is the security now, I wondered, what must it have been like before 1978, the year the Yankees famously took the American League East title from the Red Sox in a one-game playoff at Fenway Park? I walked into the clubhouse and immediately recognized the Boston equipment manager who on Opening Day in the Bronx had given me twenty bucks and sent me up the block to buy a pair of bat stretchers. Nick reintroduced us, and he pointed out the locker that he'd labeled with a strip of white athletic tape: "MCGOUGH". All the Yankees' road uniforms, which had arrived two nights before from Cleveland, had been unpacked and hung neatly in the lockers, including my own. As Jamie had mentioned, it felt odd at first to dress in a gray uniform, with "NEW YORK" printed across the front, than in the familiar pinstripes. But the road uni seemed to fit as well as the one at home. One of the visiting clubhouse attendants came over and asked me if I wanted to see the inside of the old-fashioned scoreboard set into the Green Monster, Fenway's famous forty foot tall left field wall. We walked down the tunnel to the dugout, then down the third-base line to the base of the Green Monster. There was a small door, just to the left of the window indicating the number of the player at bat, cut into the manually operated scoreboard at the bottom of the wall. Through the door was a small concrete room, furnished only with a three-legged wooden stool and a portable radio. Trays of green metal plates painted with white numerals littered the floor; they were the same size as the vacant windows in the scoreboard through which I could see a Red Sox player taking B.P. across the field. "Is he really three hundred ten feet from here?" I asked my tour guide. I thought it a trenchant question. For decades, the Red Sox had insisted that that was the true distance between home plate and the Green Monster. For just as long, opposing teams had insisted the distance was far shorter than that. It was part of the folklore of baseball in general, and Fenway Park in particular. The Boston Globe once went so far as to use aerial photography to measure the distance at slightly less than three hundred and five feet; the Red Sox ignored the exposé. "Three-ten," the clubbie told me. "Sure it is," I joked. "There's a piece of chalk there if you want to put your name up on the wall," he told me. I looked up and noticed for the first time that the raw concrete walls were adorned with hundreds of faint scrawls, names of ballplayers who'd ducked inside the scoreboard over the years to add indisputable evidence that they'd once played in Fenway Park. "Really?" I asked. "Sure," he said. "Go ahead." I picked up a piece of chalk and marked my name and the date on the wall as I high up as I could reach; I hope it's still there today. We walked back to the visiting dugout, which was still empty pending the arrival of the late bus from the hotel. The clubbie headed back inside, and I took a seat on the bench by myself to watch the Red Sox take batting practice. I couldn't get over the fact that I was actually sitting in the same visiting dugout that Joe DiMaggio and Allie Reynolds and Tommy Heinrich had in 1949; that Reggie Jackson and Thurman Munson and Bucky Dent had in 1978; that Darryl Strawberry and Lenny Dykstra and Dwight Gooden (Mets, but still, a great New York team) had in 1986, the first World Series of which I watched every single inning of every single game. The Yankees gradually filed down to the field and filled in spaces on the bench around me. The moment the Red Sox ballplayers cleared the diamond and the head groundskeeper signaled that it was New York's turn to hit, I grabbed my glove and sprinted out into the sun-swept Fenway Park outfield. I positioned myself in deep left-centerfield, the Green Monster looming large over my shoulder. The Yankee hitters took turns banging balls off the great wall; I stood at its base and tried to cleanly field the caroms. A little more than a year before, I'd been sitting in the Yankee Stadium bleachers, watching the same two teams play a late-season game, when the idea of applying to be a batboy first crossed my mind. Now I stood at the heart of one of baseball's foremost cathedrals, my name both on a locker in the visiting clubhouse and left as an artifact inside the cathedral's innermost sanctum. I was dressed in my own Yankee road uniform, catching balls hit off major league bats with a glove I'd broken in over a full major league season. I was in Fenway Park with the Yankees. I'd say I was living out a childhood dream, but I'm not sure that, even as a baseball-crazed eight-year-old, I ever dreamed just this audaciously. I couldn't remember ever feeling so happy. Just after Fenway security opened the ballpark to fans, the Yankee pitching staff emerged en masse from the dugout. The dozen pitchers loped out to left field for their daily stretching exercises. I shifted further over toward center, utterly absorbed by my surroundings and the fly balls being launched from home plate. Within a few minutes, a few hundred fans had made their way down to the wall along the third-base line, drawn to where the Yankee pitchers were stretching on the warning track. I could hear the fans shouting down to the players below them, I presumed seeking autographs. The ballplayers seemed to be having fun bantering back. As it was, though, I was more than a hundred feet away, in my own little world, and I didn't notice at first that a few of the pitchers were waving their gloves to get my attention, calling me over. They were grinning when I jogged up to the group of them. My roommate Kamieniecki put his hand on my shoulder and pointed up to the stands, about twenty feet over our heads. The fans grew quiet and craned their necks to see what was going on. Kamieniecki pointed out a very pretty girl in a high school swimming jacket who stood right up against the wall at the front of the crowd. "Matt," he announced to me and everyone else in the vicinity, "this is Teresa." I gave Teresa a shy wave. "Teresa, this is Matt," he said, draping his arm over my shoulder. "Matt's from New York." He paused for effect, then continued, his voice projecting even further across the rows of seats slowly filling with fans: "Matt, you and Teresa are both seventeen years old, and Teresa doesn't have any plans tonight after the game." The mob of fans, two hundred or more people, gawked at Teresa in the front row, and then at me down below on the outfield grass. Both of us blushed deeply. "Uh, Teresa," I shouted up at her as quietly as possible, trying to create some privacy where there was none at all to be had, "do you want to go out after the game tonight?" The crowd leaned forward, rapt, waiting for her answer. Excerpted from Bat Boy: My True-Life Adventures Coming of Age with the New York Yankees by Matthew McGough. Copyright © 2005 by Matthew McGough. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher, Random House, Inc. To receive the conclusion of Chapter 4 of Bat Boy, e-mail the author at batboybook@gmail.com. |