“Rocky Bridges looked like a ballplayer. In fact, he may have looked more like a ballplayer than any other ballplayer who ever lived. His head looked like a sack full of rusty nails, he kept about six inches of chewing tobacco lodged permanently in the upper recesses of his left cheek, and his uniform always looked as if he had just slept in it — which of course he probably had. He had a squat, muscular frame, a wire-brush crewcut, and a glower that could have intimidated Ty Cobb. He was the sort of guy who would spike his own grandmother to break up the double play. Whenever I saw him kneeing eagerly in the on-deck circle, his knobby little hands kneading the handle of his Louisville Slugger, his baggy pants hiked up to almost the midpoint of his barrel-like chest, his baseball cap cocked slightly askew and tipped to a notably unraffish angle, it would occur to me that in reality Rocky Bridges did not exist, that he was in fact a character from a Ring Lardner short story, or a punch line to a Grantland Rice anecdote, or a figment of Damon Runyon’s imagination. ” — Brendan C. Boyd and Fred C. Harris, The Great American Baseball Card Flipping, Trading and Bubble Gum Book

When Don Zimmer passed away last June after 66 years in baseball, I called him the ultimate futility infielder. Allow me to amend that, for Rocky Bridges, who died last week at the age of 87, was every bit as worthy of that title, and every bit as much an inspiration for this site. The secret of futility infielders is their ability to thrive despite their shortcomings in talent, thanks to persistence, flexibility and a command of fundamentals that go well beyond the playing field. They’re the laces that hold the leather together, the very soul of baseball.

In an 11-year major league career that included all of 562 hits, 16 home runs, 10 stolen bases and a pedestrian .247/.310/.313 batting line — yet somehow also an All-Star appearance — the limitations of Rocky Bridges’ ability were dwarfed by a persistence that allowed him to spend nearly half a century in the game. Armed with a self-deprecating wit, he was a natural in conveying to impressionable young men the message that talent and skill alone aren’t sufficient to thrive, that the need to enjoy the game, to remember that it’s supposed to be fun, is necessary to cope with its ups and downs.

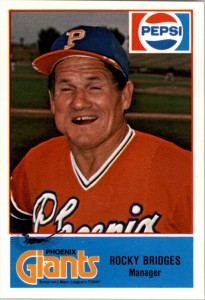

As the manager of the Pacific Coast League’s Phoenix Giants from 1974 through 1982, Bridges brought his team through my hometown of Salt Lake City (host of the Angels and later Mariner affiliates during that timespan) with regularity, and quips from the eminently quotable skipper often found their way into The Salt Lake Tribune. The passage from the Boyd/Harris book, which I stumbled across when I was 13 or 14, sketched out his back story as a fringe major leaguer, and in the late 1990s, my pal Nick Stone unearthing a used copy of the Jim Bouton-edited I Managed Good, But Boy Did They Play Bad, an anthology whose title and first chapter came from a 1964 Sports Illustrated profile of Bridges just as he was winding up the first of his 21 seasons piloting a minor league club. Writer Gilbert Rogin called Bridges “one of the best stand-up comics in the history of baseball,” and several generations of scribes who had the fortune to cover him over the years would probably agree. Rogin’s 3,500-word piece — and just about everything else written about him over the past sixty-some years — is stuffed with punchline after punchline from the former Punch-and-Judy hitter.

“I always wanted to be a baseball player. Now that I’ve quit playing, I still entertain that idea.” *

Born in Refugio, Texas in 1927, Everett Lamar Bridges grew up in Long Beach, California, where he starred in high school. He was playing semipro ball in 1947, and expecting to join the Army when his coach told him to come meet Brooklyn Dodgers scout Tom Downey. As the story goes, Bridges spent his last nickel on cab fare and came away with a $150 month contract, which he later called “the deal of a lifetime.”

“I’m the only man in the history of the game who began his career in a slump and stayed in it.” *

Bridges started his professional career in Santa Barbara of the California League. He hit just .183 with two homers in 39 games, but took up chewing tobacco on the field and smoking cigars away from it, both on the advice of a teammate who told him he’d never make the majors unless he did. The next year at Greenville, he acquired his nickname.

“A public address announcer thought Lamar sounded lousy and started calling me Rocky. For quite awhile I thought it was because of my build. Then I realized it fit my game.” **

After a year in Greenville, Bridges spent two in Montreal — where he played with Don Newcombe, Carl Erskine and Tommy Lasorda (whose curve “had as much hang time as a Ray Guy punt”) — and then made the Dodgers out of spring training in 1951, impressing manager Charlie Dressen with his grit, hustle, and an apology for missing a sign in a game in which he later hit a game-winning homer.

“I’ve been a paid spectator at some pretty interesting events… and I’ve always had a good seat. I guess they figured there was no point in carrying a good thing too far.” *

In an infield that featured Hall of Famers Jackie Robinson and Pee Wee Reese as well as Gil Hodges and Billy Cox, Bridges did not suffer from an abundance of playing time. He hit .254/.306/.328 with one homer in 147 plate appearances spread thinly over 66 game, but was a bystander during the three-game playoff with the Giants that ended with Bobby Thomson’s “Shot Heard ‘Round the World.” After playing even less the following year, batting .196/.286/.250 in 66 PA and riding pine during the Dodgers’ seven-game World Series loss, he was traded to the Reds in a four-team deal.

“The Dodgers told me I was the shortstop. I was actually about the 33rd shortstop Pee Wee Reese ran out.” **

The Reds made Bridges their regular second baseman and he rewarded them with a .227/.288/.273 showing, so they stashed him on the bench. Over the next three years in Cincinnati (“it took me that long to learn how to spell it”), he accumulated just 277 PA in 219 games.

“I got a big charge out of seeing Ted Williams hit. Once in a while they let me try to field some of them, which sort of dimmed my enthusiasm.” *

In May 1957, the Reds put Bridges on waivers, and he was claimed by the Senators, who were en route to a 55-99 record. Though defensively sound enough to play regularly at shortstop, he wasn’t much help with the bat, but in 1958, he hit a respectable .297/.356/.406 with five homers before the All-Star break, earning a spot on the AL roster — somebody needed to represent the hapless Washingtonians — for the only time in his career. Quipped Bridges, “That surprised everybody. They were close to launching an investigation.”

“I never got in the game, but I sat on the bench with Mickey Mantle, Ted Williams and Yogi Berra. I gave ‘em instruction in how to sit.” **

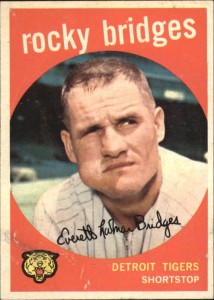

Bridges rode pine during the entire contest, which may or may not have been a factor in the AL’s 4-3 victory over the NL. Alas, in his first plate appearance after the All-Star break, an errant pitch from Detroit’s Frank Lary fractured his jaw, costing him more than a month. “It kept me from making the Hollywood scene,” Bridges said. “I was no longer just a pretty face.” He hit just .160/.186/.202 in 97 second-half plate appearances, taking the shine off his first-half numbers. That winter, Bridges was traded to the Tigers as part of a six-player deal that also included Eddie Yost. He took over as Detroit’s starting shortstop but hit just .268/.320/.349 for a team that finished 76-78. He hardly played at all in 1960, accumulating just 34 PA across three teams, the Tigers, Indians and Cardinals.

“I’ve had more numbers on my back than a bingo board.” *

In January 1961, the expansion Los Angeles Angels — Bridges’ sixth team in a five-year span — signed him as a free agent. They kept him busy enough to accumulate 259 plate appearances in stints at second base and shortstop. After he broke a homerless drought of more than two years, he told reporters, “I’m still behind Babe Ruth’s record, but I’ve been sick. It really wasn’t very dramatic. No little boy in the hospital asked me to hit one. I didn’t promise it to my kid for his birthday, and my wife will be too shocked to appreciate it. I hit it for me.”

“The main quality a great third base coach must have is a fast runner.” ***

Bridges’ age (33) and typically light bat suggested he had little future in the majors, so he retired following the season (“I think they asked me to”), but having maxed out at a salary of $12,500, it wasn’t like he had riches to fall back upon. This was a man who spent various offseasons pouring centrifugal die castings for a foundry, cleaning out furnaces and sacking soap for Boraxo, running a jackhammer or digging ditches. He took a job with the Angels as their third base coach, and served in that capacity under manager Bill Rigney for two years; the team even enjoyed a burst of success, going 86-76 in just their second season. In 1964, Bridges took over as manager of the team’s High-A California League affiliate, the San Jose Bees.

“I was sent down here to learn the pitfalls of managing—not winning.” *

The Bees’ roster at various points featured 13 future major leaguers including longtimers Tom Burgmeier and Jay Johnstone. The latter left an impression; throwing batting practice without benefit of a screen, Bridges was hit on the knee with a line drive and left with a permanent limp. He guided the Bees to a 73-67 record, good for third place in the eight-team league, but more important than their standing was his role in developing players, which started with making sure they were enjoying their opportunity. “The umpire says ‘Play Ball,’ right?” he reminded. The lessons of his first season are all over Rogin’s SI feature.

“I try to dream up strategy and things on third—like please hit the ball. The first game I managed good, but boy did they play bad.” *

Bridges enjoyed similar success in two more seasons at San Jose and one with the Double-A El Paso Sun Kings, whose roster featured future free agent cause celebre Andy Messersmith, future Gold Glove winner Auerlio Rodriguez and future colleague and PCL managerial rival Moose Stubing. According to legend, one night while coaching third base, El Paso’s Ethan Blackaby homered. In shaking his hand as he rounded third, Bridges pressed a wad of wet tobacco into Blackaby’s hand. Blackaby took it in stride, then handed it off to a teammate at home plate — who nearly fainted.

“You mix two jiggers of Scotch to one jigger of Metrecal. So far I’ve lost five pounds and my driver’s license.” ****

Bridges returned to the Angels as their third base coach, spending four seasons (1968-1971) in that capacity under Rigney and successor Lefty Phillips. He went on to join the Padres’ organization, spending a season and change managing the Triple-A Hawaii Islanders of the Pacific Coast League. In a scene straight out of Bull Durham, he gave away the bride of pitcher Ralph Garcia in a marriage ceremony conducted on the mound between games of a doubleheader.

“There are three things the average man thinks he can do better than anybody else: build a fire, run a hotel and manage a baseball team.” *

Bridges didn’t last long into the 1973 season with the Islanders, but that year saw Rogin’s feature immortalized in the anthology edited by Bouton and Neal Offen, which came about as Playboy Press tried to capitalize on the success of Ball Four. In introducing “I Managed Good,” Bouton called Bridges his all-time favorite manager while admitting that he’d not only never played for him, but never met him, either. “However, I’ve spent a good piece of my life sitting in bullpens around the county listening to different ballplayers talk about how much fun it was when they played for Rocky Bridges,” Bouton wrote, recounting a tale where the skipper tried to shake things up by giving signs from the third base box while standing on his head, noting that Blackaby (again at the plate) had to stand on his head to receive them. The tale may be apocryphal, to say the least. 1973 also saw Bridges included in The Great American Baseball Card Flipping, Trading and Bubble Gum Book.

“We’re about three blocks from hell in the summertime.” *****

In 1974, Bridges landed another job in the Pacific Coast League, this time with the Phoenix Giants, whose general manager was none other than Blackaby, a mere 33 years old but past a nine-year professional career that included just 15 games in the majors. Bridges earned Manager of the Year honors while guiding the Giants to a 75-69 finish, good for fourth place. That was the first year of a fruitful nine-year stint aided by Blackaby purchasing an interest in the team. For the first eight years of that run, Bridges would regularly walk three miles from his hotel to Phoenix Municipal Stadium; during the ninth, he took up residence in the (air conditioned) clubhouse.

“I don’t know how to spell Albuquerque but I sure can smell it.” **

In 1975, Bridges’ team opened the season in the PCL’s New Mexico outpost. He drew boos from the crowd for using the city as a punchline, but turned them to cheers by hobbling to the plate and then doing a headstand.

“Seems to me that when you manage in the majors, all you’re really doing is walking out on the gangplank and waiting for the guy with the sword to come and poke you in the butt.” *****

At the end of the 1976 season, Bill Rigney — who had come out of retirement to manage the Giants — stepped down. Owner Bob Lurie quickly settled on Joe Altobelli, who had piloted the Orioles’ Triple-A affiliate to four first-place finishes in six years, to replace him; Bridges received an interview, though he believed it was merely a courtesy call. He refused to campaign for the job and at 53 years old, realized a big league posting might never come. Undaunted, he led Phoenix to the 1977 PCL title and earned another Manager of the Year award. He had his bad days as well. Pitcher Greg “Moon” Minton, who spent four seasons shuttling between Phoenix and San Francisco at the start of what would eventually become a 16-year major league career, recounted a couple of rough outings, including one where he gave up seven first-inning runs:

“He comes storming out there and growls, ‘Give me the ball.’ I step back. He looks and says, ‘Dang thing is still round.’ He gives it back to me and walks away.

Another time, Bridges came to the mound, folded his arms — back to the bullpen — and said, “Moonie, look over my left shoulder.”

“I don’t see anything, Rock,” said the pitcher.

“That’s right,” said Bridges. “You’re here for the rest of the game.”

“If it was raining nickels, [that pitcher]’d be in jail. If it was raining camel crap, he’d be in the middle of the field without a number.” *****

After graduating cogs like Jack Clark, Larry Herndon, Ed Halicki and Bob Knepper to the majors in the first few years of his tenure, Bridges’ Phoenix club fell on hard times, posting the league’s worst record in both 1979 and 1980. Still, he persisted with his sometimes unorthodox style. As Pete Weber, the voice of the Albuquerque Dukes, recounted, “Rocky’s signs were simple. He realized that it was all about execution, and not necessarily trying to fool the opposition. For a steal, he might whistle at the runner and point to second and sometimes yell, ‘go!’ for good measure. He sometimes called for a bunt by squaring around with an ‘air bat’ in the coach’s box when the batter checked in.”

“This is kind of like putting earrings on a pig, isn’t it?” ******

Bridges left Phoenix following the 1982 season but remained in the Giants organization as a scout and manager of the Short Season-A Everett Giants. “It was nice of the Giants to send me to a town that was named after me, “he said later. “I’d call in my reports and sign off, ‘This is Everett from Everett.'” In 1985, he joined the big club as the third base coach under manager Jim Davenport, who didn’t last the season, a dismal one in which the Giants finished 62-100. He moved on to the Pirates organization, managing at Class-A Prince William in 1986, Triple-A Vancouver in 1987 and then Triple-A Buffalo in 1988. Weber worked for those Bisons, and remembered the day Bridges was introduced. “It may have been the only time I ever saw him in coat-and-tie. He made it clear that wasn’t part of his look,” he said, hence Bridges’ porcine quip.

Veteran writer John Perrotto (a former colleague of mine at Baseball Prospectus) got his start covering the Pirates the year Bridges took over in Buffalo, and remembers the grizzled manager making an impression in spring training “with the big chaw, the limp and a weather-beaten face,” not to mention the sense of humor: “The one thing I do remember him telling me, and it’s stuck with me to this day is — you better enjoy yourself because it’s a really long season. If you’re not having fun along the day, it’s going to be a miserable six months.”

“Hey. Casey. What’re you about to do?” ********

After Buffalo, Bridges managed for one more year at Class-A Salem, then worked until 1994 as the Pirates’ roving infield instructor. That last year, he served as a de facto bench coach for the Welland (Ontario) Pirates of the New York-Penn League, mentoring 30-year-old rookie manager Jeff Banister, who at this writing is about to launch his first season as the Rangers’ major league manager. At a recent Coaches Clinic at Rangers Ballpark, Banister cited Bridges influence, telling a story of a time he leaped off the bench with the intention of hollering at his players, only to be talked down by the grizzled 67-year-old.

“Up here, they didn’t know a damn thing about me, so I could tell them how great I was.” *******

After that seasons, Bridges retired to Coeur d’Alene, Idaho, where he had moved his family — wife Mary and children Mindy, Lance, Cory and John — in 1970. In all, he’s credited with a 1381-1432 record during his minor league managerial career, but more important than the wins and losses was the message he passed on to his players at every stop:

“You got to make the big show, kid. It’s the only letterman’s sweater to have.” *****

Thanks to the aforementioned books and his gift of gab, Bridges remained in circulation even in retirement. The internet is filled with his stories as recounted by dozens of writers, and there’s no shortage of Bridges memorabilia on eBay. Years ago, as this site picked up steam, I myself scored a 1955 Bowman card of his that was allegedly personally autographed, and also an Adirondack 282J Little League “Rocky Bridges” model bat that looks as though it had been brined in tobacco juice for two decades — items that together may not have been worth the $20 I paid for them, save for the reminders of what Bridges meant both to me and to the baseball world.

In the end, there are All-Stars and record holders who probably didn’t leave half the mark on the game that Rocky Bridges did. Talent can take you a long way, but as he showed, persistence and wit can take you even further.

Quotation sources:

* Gilbert Rogin, “I Managed Good, But Boy Did They Play Bad,” Sports Illustrated, August 18, 1964

** Ross Newhan, “The Return of Rocky: A Welcome Sequel,” Los Angeles Times, March 25, 1985

*** (Uncredited) “Only the Game Has Changed,” Sports Illustrated, May 10, 1971

**** (Uncredited) “Scorecard,” Sports Illustrated, August 2, 1971

****** Pete Weber, “Weber remembers the late Rocky Bridges,” MiLB.com, January 31, 2015

******** Jamey Newberg, “The importance of Rocky Bridges,” The Newberg Report, February 4, 2015

Pingback: Rocky Bridges, part 2 | KristJake.com – views on the landscape

Great story !!!!