As I’ve said before, I’ve often traced my yen to write about baseball back to my paternal grandfather, Bernard Jaffe. Last Tuesday, May 20, marked his centennial birthday, and with my various deadlines and other obligations out of the way, I’d like to honor his life and share some fond memories.

Bernard — “Bernie” or “BJ” to friends, “Poppy” or “Pop” to me — was a lifelong baseball fan who witnessed a marvelous swath of baseball history over his 92 years of life. When I was a youngster, he regaled me with tales of seeing the “Murderer’s Row” Yankees of Babe Ruth and Lou Gehrig, Giants such as Mel Ott and Bill Terry, and the daffy Dodgers, who became his team after he watched star outfielder Babe Herman get hit on the head with a fly ball he was attempting to catch. To him, the underdog and occasionally hapless Bums of Brooklyn offered an appeal that the Giants, class of the National League for so many years, couldn’t match. Even after departing Brooklyn to move across the country more than a decade ahead of the Dodgers, he passed on his allegiance to his sons and grandsons.

I was Pop’s first grandchild, and I believe he always found something in me that he could connect with. While fully capable of being outgoing, both of us at heart were introverts, and we shared a similar love for reading. In addition to his oral history lessons, Pop encouraged me to read about the game, and not just via the pallid biographies written for kids. I vividly remember the day a box of secondhand paperbacks he’d rescued from the flea market arrived at my Salt Lake City home. At nine years old, I was reading Roger Angell’s erudite essays in a dog-eared copy of The Summer Game and parsing the more complicated swear words in a musty edition of Jim Bouton’s Ball Four. Those two books in particular introduced a self-awareness which shaped my powers of observation and eventually, my writing while rendering schoolboy fare like All-Pro Baseball Stars 1979 obsolete.

• • •

Born in Brooklyn on May 20, 1908 as the third of four boys, Pop rarely spoke his childhood, which wasn’t the happiest. His father was a master tailor and a rabble-rouser who at various times in his career was blacklisted because of his efforts to unionize the garment factories in which he worked. Emotionally, he was a cold man, who didn’t provide much overt affection. From what I understand, at some point he walked out on his family, though it wasn’t until later that he obtained a divorce and remarried. Though I’m sure the era had something to do with the way he was raised, Pop took the counter-example of his own life to heart; he was a warm, generous, devoted family man and a pillar of his community.

This is him as a young boy, with mother Dora on the left, c. 1915:

Though only a wiry 5-foot-8 1/2, Pop was an excellent athlete. He played baseball at the University of Maryland, and was said to have been offered a professional contract, but he had other ideas about what he wanted to do in life. He got a graduate degree as a pharmacist, and worked for six months in Baltimore while hustling pool at night to help save up enough money to attend medical school. Unable to afford the exorbitant cost of attending a stateside medical school, and stymied by the quota system which limited the number of Jews, he managed to start his studies in — of all places — Hitler’s Germany, at the University of Göttingen. The chutzpah! He didn’t know much German when he came over, but he learned the language by reading newspapers and walking the streets. He somehow managed to wrangle a ticket to the 1936 Olympics in Berlin, where he saw Jesse Owens show up Hitler by winning four gold medals.

Standing to the left of brothers Hank and Matty, this picture shows Pop in a rather streetwise pose, as though waiting for his next mark to show up to the pool hall. It’s dated 1936, but I believe it’s a bit earlier, from before he went overseas:

After a year at Göttingen, he was advised to leave, and he transferred to the University of Vienna, where he met Clara Gottfried (1912-2006), a woman four years his junior but a year ahead of him in medical school (“Nanny” or “Nan” to me). They met one Saturday night while she was studying for an exam in a coffee house; he was playing pool, saw and recognized her, and offered to walk her home. They married in Vienna on March 29, 1938, and with the situation there worsening vis-à-vis the Nazis, began planning their exit. When he finished his studies, Bernard didn’t even wait around to receive his diploma; a classmate named Dr. Samuel Schoenberg picked it up along with his own, and escaped by walking over the Alps into Switzerland.

Bernie and Clara in Vienna, 1938:

Thanks to the efforts of an American cousin of her father named Marcus Helitzer (who opened an American bank account in her name with $1,000), Clara was granted a visa to travel to the US. The couple booked passage on a ship and arrived in the US on July 15, 1938, but Clara never saw her parents again. Both died in concentration camps, as did nearly all of my grandmother’s relatives.

Stateside, my grandparents settled in New York City. Bernard got an internship at Brooklyn Lutheran Hospital, living on hospital grounds while Clara lived out on Long Island with the Helitzer family, and they saw each other on weekends. She got a job working as the physician for a girls’ camp in Liberty, New York, and soon earned enough money to get an apartment of her own on 86th Street. He entered the Army Reserves in 1939, and she took over his internship, having passed her medical boards in April.

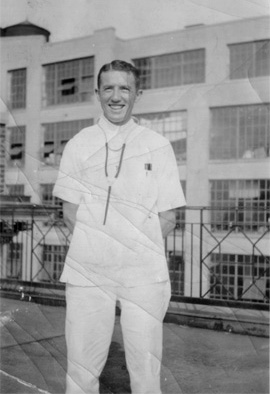

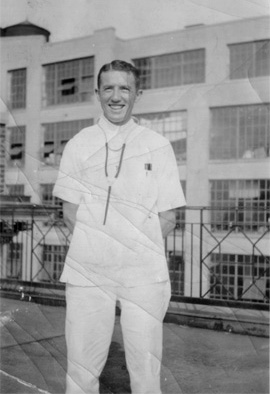

What’s up, Doc? Bernie on the grounds of Brooklyn Lutheran in 1939:

When Clara completed her internship, Bernard asked her to join him down in Asheville, North Carolina, where he was the physician at a Civil Conservation Corps base. In those uncertain times, he wanted her to settle down and to start a family. He got his first position in Hot Springs, outside of Asheville. When the Reserves called him up for active duty, he failed his physical. The story goes that he’d been playing tennis and, not having a car, had run several miles to the offices. When he arrived, he was sweating profusely. The doctor asked if this happened often, and when he said yes, the doctor feared he had a cyst. He was turned down for active duty and sent to Augusta, Georgia to train for the Veterans Administration hospital. There, my father (Richard) was born in 1941.

Bernie and Clara, 1940 in Miami:

With my dad at about one year old, 1942:

They bounced around — the life of an Army doctor — finally settling in the farming town of Walla Walla, Washington in 1944; they had another son, Bob, in 1946. While my grandmother adapted to life as a homemaker, my grandfather made his practice as an otolaryngologist (ear, nose and throat doctor), and practiced at the VA hospital there until his retirement in 1973. Upon leaving the VA grounds, they bought a house at 1966 Scarpelli, and he lived out the rest of his life there. When he retired at age 65, Pop didn’t think he had many years left to live; the average life expectancy at the time was only about 73 years old. Instead he managed to live another 27 years, long enough to see all four of his grandchildren grow into early adulthood.

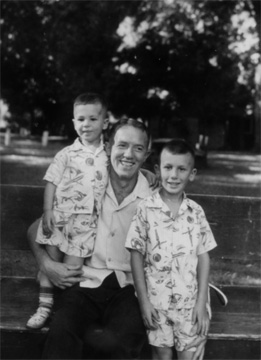

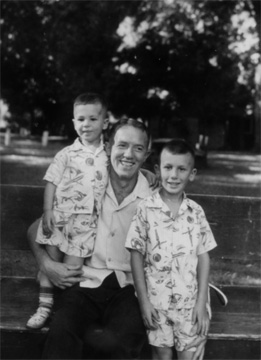

With both of his kids, 1949:

• • •

I spent many a wonderful summer day with Nan and Pop. They would drive down to our home in Salt Lake City, and after a visit of about a week, would drive us back to Walla Walla; Pop would his massive gas-guzzler (a Cadillac Seville, I think) drive the entire distance in one 12-hour day, and we’d stop for dinner at Sizzler about an hour or so outside of town. We’d spend as long as three weeks in Walla Walla, then my parents would meet us there or we’d rendezvous at a family reunion on the Oregon coast or at the Black Butte Ranch, near Sisters, Oregon.

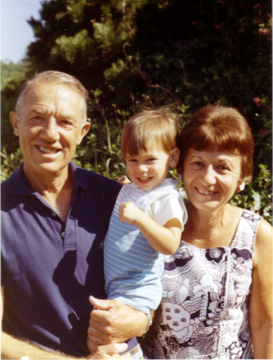

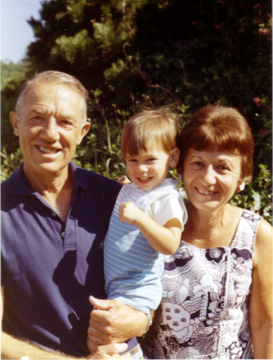

With their first-born grandson (me), 1971:

Pop gave me my first ball glove, an occasion that remains etched in my memory, a warm summer evening when I was about seven. Instead of playing whiffle ball in the backyard as we regularly did with my father, my brother and I were instructed to put the mitts on our left hands. We struggled to grasp this fundamental puzzle just as surely as we did the balls Pop and Dad lobbed to us from a few paces away, but gradually we got the hang of it.

Dad usually had time to play catch or Hot Box with my brother and me on a regular basis, but when we stayed with my grandparents, we were in baseball immersion camp. In the morning Pop and I would walk down to the grocery store to get the morning paper, The Oregonian, and we’d read the boxscores and game summaries on the way home. After that we’d collect my brother and go to nearby Howard Tietan Park, where Popwould pitch to us from behind home plate as we’d smack balls, five a turn, into a backstop where one rung meant a single, two a double, three a triple, and over the backstop a home run (just this past winter I discovered that this was actually an old stickball variant). When the balls got too beat up from bashing into the chain links of the backstop, Pop covered them in electrical tape and we’d hammer them until they resembled squeezed grapefruits.

We’d also play catch in his endless backyard; he’d throw long balls and we’d chase after them, laying out for “spectacular catches,” the name we gave that particular drill. We’d play in his huge garden; while he would spend endless hours picking enormous raspberries (which Nan would turn into delicious jams), we’d throw the various fallen fruits and vegetables into an oversized barrel of dirt and compost which we called “elephant stew.” In the evening we’d watch baseball on his new-fangled cable TV system, which included the fledgling ESPN station. My brother and I would sit on the arms of Pop’s big red leather chair. Often he’d turn the volume down and play classical music while talking to us as the game went on, perhaps breaking out a crossword puzzle, a favorite pastime, and pitching us the easy clues while explaining the harder ones in an effort to expand our vocabularies.

Once in awhile, we’d go see the Walla Walla Padres, the Low-A Northwest League affiliate of San Diego, play at Borleske Stadium. I watched a handful of players who would leave their marks in the majors in some way or another come through Walla Walla, including Tony Gwynn, John Kruk, Mitch Williams, Jimmy Jones, Kevin Towers, Greg Booker, and Bob Geren. The league featured opponents like Mark Langston and Phil Bradley of the Mariners’ Bellingham squad as well. Even then I kept score at those games, and I still have the those programs. In the summer of 2006, I served as the consultant for a bobblehead commemorating Gwynn’s 42-game stay with Walla Walla in 1981, to be issued the following year in celebration of his induction into the Hall of Fame.

As I got older, the visits to Walla Walla inevitably stopped; the last year I recall us staying with them was 1982, which as it turns out was also the last year the Padres were in town. In retrospect, I realize how lucky my brother and I were to share so much time with my grandparents; my cousins, who are five and seven years younger and lived much closer in Seattle, didn’t get the same mass quantity of quality time, didn’t know them in the same way.

We still saw Nan and Pop a couple times a year in Salt Lake City, and talked on the phone every couple of weeks. Every so often, another box of books would arrive, more baseball to bind us together. The calls grew less frequent as Pop’s hearing seriously declined; he never really adjusted to wearing a hearing aid, often turning the accursed thing off and missed out on a lot of the conversation. Nonetheless, he was still pretty sharp into his late 80s; not until various physical maladies, including prostate cancer, began taking their toll did the quality of our conversations really take a downturn.

I last saw my grandfather in 1999, when I visited Walla Walla with my parents. He was frail, stooped, and using a walker, a shadow of the vital man I’d once known. I recall that we watched a few innings of a ballgame together, seeing the Yankees’ Orlando Hernandez get knocked out of the box against the Mariners in newly-opened Safeco Field. Later that day, he gave me a prized possession I knew had been coming my way for quite some time, a vintage Rolex watch that he’d owned for 50 years, squirreling away for a day when he cold pass it on. It’s a beautiful, timeless timepiece; I still think of him every time I wear it.

Pop passed away quietly on November 24, 2000, the day after Thanksgiving. I flew to Walla Walla and joined my father, uncle and brother in delivering eulogies and serving as a pallbearer. My grandmother would survive until August 2006, sharp into her early 90s; I wrote about her passing here.

• • •

Four and a half months after Pop passed away, one of my baseball favorites, Willie Stargell, died as well, and it brought back a flood of memories of Pop, Bryan and I watching the 1979 “We Are Family” Pirates, who were all over the airwaves that summer on their way to a World Championship (the Dodgers, coming off consecutive pennants, were stuck in sub-.500 oblivion). Moved by Stargell’s passing and, in the tradition of my grandfather, struck with a yearning to pass on a generation of baseball wisdom to those whose appreciations didn’t go back as far, I wrote an obituary of sorts, and emailed it around to friends. It became the cornerstone of the Futility Infielder website.

In two weeks time, I’d registered a domain name, opened a Blogger account, and bought a book on web site design. The rest is history, my history. For as much as I was able to glean from my grandfather, there are many times I’ve found myself wishing he’d kept a memoir of the players and the games he saw. They would have provided me more insight into the man, as well as those times, and his keen eye and dry wit would have been preserved for posterity. So it is that I record my own thoughts and descriptions in the hope of sharing my interest in the Mendoza Line, the 1998 Yankees, and the games of today. The arcane and the amazing as well as the now, a flowing river of baseball history that began with a man born a century ago.